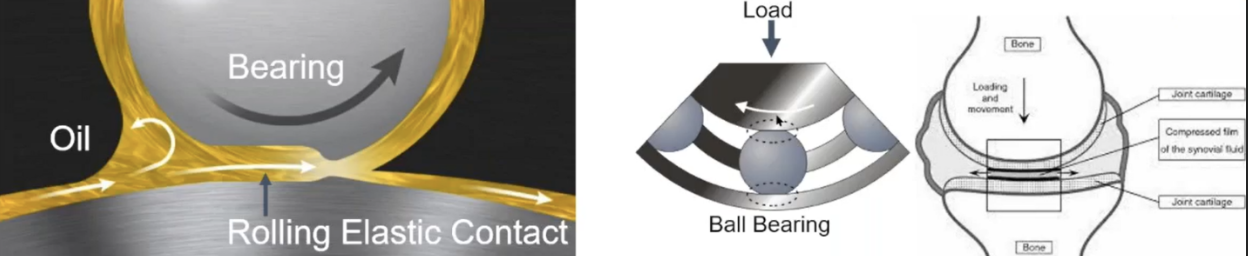

Elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL or EHD) is a type of lubrication regime used for high-pressure applications such as bearings that carry heavy loads. For example, the bearing shown in Figure 1 is under a highly concentrated load.

Figure 1: Bearing under heavy load, compared to knee joint

Highly concentrated loads create a wave of metal ahead of the load zone. The rolling elements and the race elastically deform to enlarge the contact area. This elastic deformation is the bearing’s fatigue cycle.

Let’s say there are eight roller balls in a 1,000 RPM bearing. This means there are 8,000 fatigue cycles, or shocks, happening inside the bearing. As a roller enters the tight area of the loaded bearing, it will generate a deflection wave. The resulting shock pulse will push at the metal. If you drop a marble into a bowl of water, the metal deflection deforms in concentric waves like those ripples of water.

One factor will determine whether the bearing will survive these fatigue cycles—the lubricant film. The same goes for gears meshing at the load zone, cams and sprockets, and chain contacts.

Whenever two mating surfaces are being pushed against each other, which happens in all of these applications, we get elastohydrodynamic lubrication. “Elasto,” because something is happening based on the elasticity of the metal. When the metal deforms, it provides space to allow the lubricant to work properly.

The rolling element mating will generate a pressure up to 500,000 psi. This is a huge pressure compared to the area and the thickness of the lubricant film. The lubricant film may be 1 or 3 microns, in the best cases, sometimes up to 5 or 6 microns, but no more. This is tiny. One particle of baby powder is around 10 microns. One particle of cigarette smoke is 1 micron.

So imagine how slim that lubricant film is, which is responsible for managing the life of your bearing and reducing friction-related energy loss. And the lubricant film has a very small space to work in, under humongous pressure.

If a small particle, or some water, were to get into that lubricant film, what would happen? The bearing would be catastrophically damaged, very quickly.

At this point, you may be thinking, why not add a more viscous lubricant? Viscosity is the most important property of oil, but to double the thickness of an EHL film from 1 micron to 2 microns, you would need four times the viscosity. This means if you’re using a viscosity grade of 100 centistoke, you would need 400 centistoke.

If you dramatically increase the viscosity, your bearing will become really hot. And this will cause problems. So this is not the solution. There must be another way.

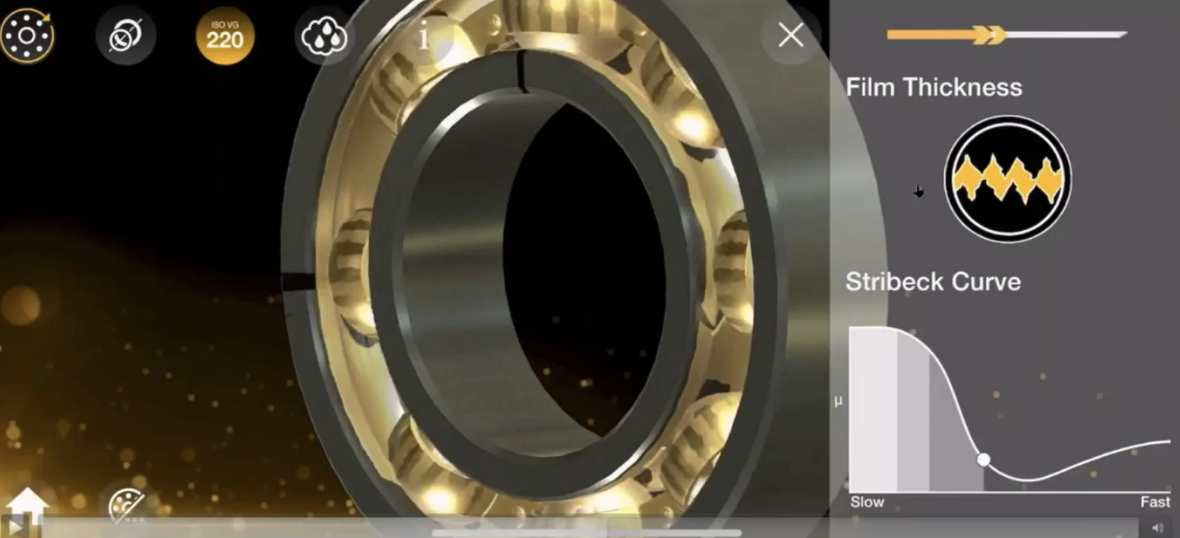

We use the Stribeck curve to understand what is going on in the bearing and what kind of lubricant it needs. It illustrates the relationship between a lubrication parameter and the friction coefficient. Velocity is a factor since it impacts friction.

Figure 2: The Stribeck curve

If we were to increase the speed of the bearing in Figure 2, knowing the film thickness, we would see an ideal point at which the bearing should operate. The lubricant film should be just thick enough to separate the bearing surfaces.

Note that the bearing surfaces are not smooth. If you were to take a microscope, even a cheap one, and magnify the bearing surface by 1,000 or 5,000, you would be surprised by the topography the surfaces have. They’re like mountains and valleys.

Figure 3: Magnified bearing surfaces

What happens, then, if there is not sufficient lubricant? The tips of the peaks will heat up, and there will be mass transfer, adhesive wear, and abrasive wear.

Abrasive wear happens when the softer metals come loose, and there are tiny metal shards flying around in the machine, causing more damage. Adhesive wear happens when surfaces stick together and become “cold-welded,” and they have to be broken apart by torque.

Both of these forms of wear will kill your machine. And both of them are completely preventable with proper lubrication practices.